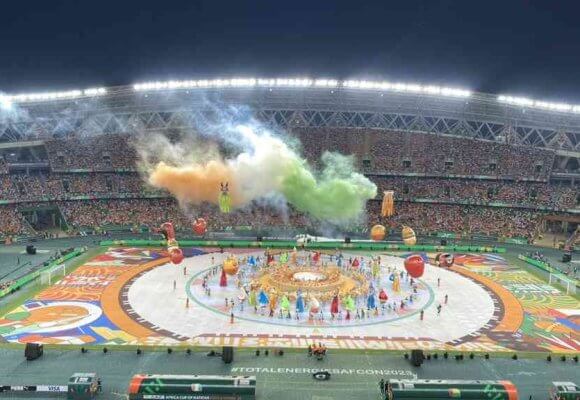

It has been a history-making World Cup in Qatar for the five African teams. For the first time, all representatives won at least one match, the best performance in the 92-year history of the competition.

But one cannot help but wonder if the story would be any different if all the talented players of African descent had elected to represent these teams. After all, they have a genuine link to the said team, which is all FIFA requires.

Historically, European and South American teams have won every one of the 21 World Cup titles so far, with 12 for Europe and nine for South America. No team from another continent has made a final in nearly 100-year World Cup history.

Before the 2022 edition of the global showpiece, 82 of 84 semi-finalists had been European or South American. The United States in 1930 and South Korea in 2002 were the exceptions.

But Morocco is out to change the narrative. The Walid Regragui-led Moroccans defeated Portugal in the quarter-finals to become the first African country to reach the tournament’s last four and are a win away from breaking yet another glass ceiling to reach the final. However, they face the herculean task of playing a star-studded French side.

The match scheduled for Wednesday, December 14, has revived a heated and sensitive conversation about African immigrants. Others have elected to make it a subject for banter referring to the French team as the “African” representative with Morocco as the “European” side.

So sensitive is the matter, so much so that Morrocan player Sofiane Boufal was forced to apologize for failing to mention Africa in his post-match interview after the Atlas Lions defeated Spain in the last 16 to qualify for the quarters.

Boufal had said that their win, coming through post-match penalties after a goalless draw in 120 minutes of regular and extra time action, was for Moroccans worldwide, the Arab nation, and Muslims.

There have been many conversations on whether Boufal chose not to celebrate his Africanness or it was an honest mistake. However, the list of “African” players that have elected to represent countries on other continents for various reasons is endless.

It is, however, essential to note that theirs is not a case of nationality- shopping. These players have genuine links to these teams, most having been born in said countries to parents of African heritage.

There is a strong and undeniable imprint of African immigration in Qatar. So, who are these players, and where would they be playing if they had chosen to play their football for ‘Mama Africa?’

Switzerland’s Breel Embolo found himself on the spot in the group stage matches in Qatar when he had to face his country of birth, Cameroon.

The 25-year-old Monaco forward scored his first World Cup goal against the Indomitable Lions three minutes into the second half of Switzerland’s opening fixture but he chose not to celebrate and instead raised both hands appearing to apologize.

Embolo was born in Yaoundé before moving to France with his mother at the age of five where she met her Swiss husband. Embolo received his Swiss Citizenship in 2014, and after featuring for their Under-16 side, he committed his international allegiance to Switzerland in December of that year and has since earned more than 50 caps.

The France national team represents the best case of immigrants’ contribution to football. In 2018 when Les Bleus won their second World Cup, 20 years after their first, South African comedian and political commentator Trevor Noah, then hosting an American late-night talk show and satirical news program, The Daily Show, came under fire for an ‘Africa won the World Cup’ joke.

This, however, was not something new for the French team as their win in 1998 saw the slogan Black-Blanc-Beur (Black, White, Arab) coined to describe the multi-ethnic team.

In Russia 2018, more than ten of the 23-man squad members for Les Bleus were of African descent. The script is no different in 2022 with the 26-man squad in Qatar.

In the two editions, Kylian Mbappe has been an integral part of the French team. While he was born in Paris, the PSG ace has never denied his African origin. He is the son of a Cameroonian father and an Algerian-born mother.

His teammates, centre-back Jules Kounde who plays for Barcelona could have featured for Benin, William Saliba for Cameroon, centre-back Dayot Upamecano for Guinea-Bissau, Liverpool’s Ibrahim Konate for Mali, Axel Disasi, the 24-year-old Monaco centre-back for Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) or Angola (he was called up for DRC’s Under-20 team in 2017).

Others in the Didier Deschamps-led team are 22-year-old Real Madrid midfielder Aurèlien Tchouameni who has roots in Cameroon, Eduardo Camavinga for Congo.

Mattèo Guendouzi, born to a Moroccan father, would be going up against Les Bleus on Wednesday in the semis had he elected to represent the Atlas Lions; maybe, Youssouf Fofana for Mali, Randal Kolo for DRC and we might as well add the injured Karim Benzema for Algeria.

Reserve French keeper Steve Mandanda holds dual Citizenship for France and DRC. The 37-year-old was born in Kinshasa. His brother Parfait is a DRC national team keeper.

Steve has earned the nickname “Frenchie” amongst his relatives for having chosen to play for France rather than his country of birth.

Away from Les Blues, the case of Timothy Weah cannot go unnoticed. After all, it is not every day that a president’s son plays for another country and continent on the biggest footballing stage.

Twenty-two-year-old Timothy, son to Liberia’s 25th president George Weah, a former footballer and the only African Ballon d’Or winner, represented the United States in Qatar, scoring in his World Cup debut against Wales.

The Lille forward was born and raised in New York to Weah and his Jamaican mother. Timothy featured in US’s Under-15, 17, 20, and 23 sides before making his senior debut in March 2018. He was eligible to represent Liberia, Jamaica, and France but chose the US.

Timothy’s teammate Haji Wright also has Liberian roots, while 20-year-old Yunus Musah, who was also eligible to represent Italy, England, and Ghana, chose the US.

Musah represented England at the youth level and appeared set for an international future with the Three Lions, but the US convinced him to switch allegiance.

The Netherlands squad also has notable names led by Nathan Ake, whose father, Moise, is from Ivory Coast. It was rumored that he would represent the Elephants in international football, but ultimately, he chose the Dutch.

Sensational Cody Gakpo could have played for Togo or Ghana, while Memphis Depay has roots with the Black Stars.

Without the mention of Bukayo Saka, the list of prominent World Cup stars with African roots is incomplete. The 21-year-old was a star on his debut at the World Cup for Three Lions. He was born in London to Yoruba Nigerian parents. He represented England from the Under-16, making his senior debut in 2020.

Other notable players in the long list are Antonio Rudiger, who grew up in Berlin, born to a Sierra Leonean mother. Although there was never any doubt that he would represent Germany, the center-back has invested heavily in the West African country.

Jamal Musiala snubbed both England and Nigeria to represent Germany, as did Leroy Sane, the son of former Senegal international Souleyman Sane, and could have represented the Lions of Teranga.

Not forgetting the case of the Williams brothers Nico and Inaki, both at Atletico Bilbao. Both competed in Qatar, with the younger brother representing Spain while Inaki played for Ghana.

Inaki played for Spain at the youth level before struggling to gain a senior call-up despite his form in La Liga, and earlier this year, he decided to switch his allegiance to his parent’s birth country.

Hosts Qatar had their fair share of an African imprint at the World Cup that has seen 136 players representing countries other than the ones in which they were born (a different statistic from the African imprint aspect).

While the African teams fielded many foreign-born players, with Morocco leading the statistics, it is undeniable that the continent’s lack of structures has led to players choosing to play for other countries over their African alternatives.

These countries have well-structured academies and professional clubs, which cannot be said about Africa.

The children of African migrants there pass through the system to become good players and elect to represent said countries. However, the competition at the very top in these countries is fierce, and while some players of African descent get the chance to represent their countries of birth, many more become available to play for African teams.

While we debate and celebrate whether an African or African-dominated team will play in this year’s World Cup final, the continent’s stakeholders have to make playing in Africa lucrative, whether at the club or international level.

It’s a conversion Africa can no longer ignore.