|

LISTEN TO THIS THE AFRICANA VOICE ARTICLE NOW

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

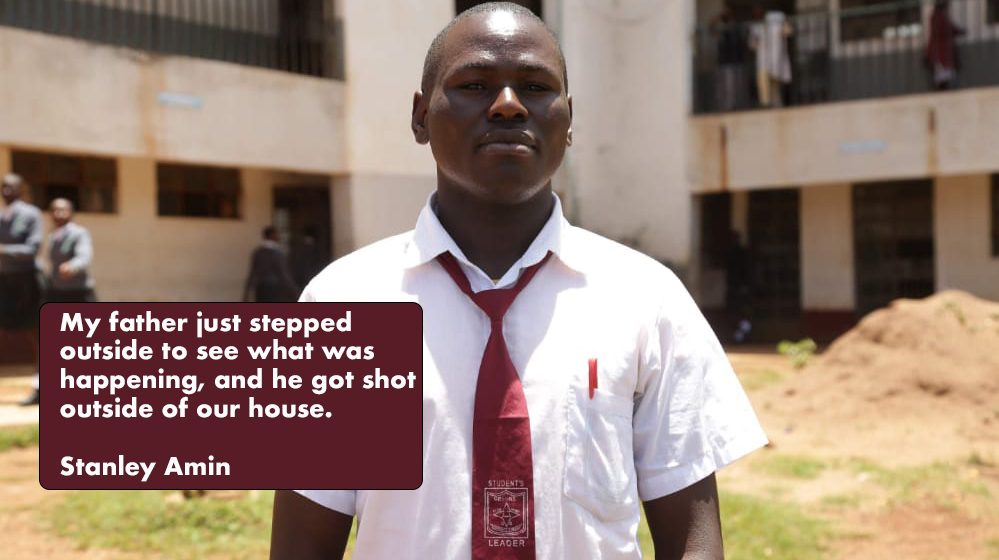

On a certain hot afternoon, in the streets of Naivasha, Stanley Amin, then eight, saw his father die in a pool of blood. He had been shot by the police.

Amid the unrest and commotion in the posh municipality of Nakuru County, Amin’s mother fled and abandoned her 3 children. Amin, now 22 and in form three, remembers the incident vividly.

“After the (2007) election results had been announced, and Kibaki declared the winner, my father became very happy because he hated Raila,” Amin said.

Amin’s said his family lived in a plot dominated by members of the Luo community who supported former Prime Minister Raila Odinga’s presidential candidacy. Therefore, his father’s utterances annoyed the neighbors. Soon, the hatred of different communities morphed into unrest, and chaos flared when they could no longer contain it.

“My father just stepped outside to see what was happening, and he got shot outside of our house,” Amin said.

His mother, whom he recalls as Susan Aoko, sensing danger, hurriedly stepped out and fled the ensuing melee.

“She didn’t carry my two younger sisters from the house. Instead, she grabbed her purse and jumped out. However, before she could run away, I held onto the hem of her skirt and asked: Mummy, where are you leaving us? She didn’t return a word. Instead, she hit my hand off her cloth and disappeared,” he recalled.

Since that day, Amin has known no father, mother, or siblings. They vanished in the somber cloud that had befallen their neighborhood.

Determined to live on and hoping against hope, Amin said he has lived in 15 different homes since then. In some places, he has been greeted with stern unwelcoming faces, and in others, overwhelming hospitality from strangers has instilled hope that there is hope and life can be favorable somewhat.

“My father just stepped outside to see what was happening, and he got shot outside of our house,” Amin said.

But, more often than not, life has dealt him violent blows.

He has done all he could to trace his relatives with no success.

Before going to Naivasha, Amin’s mother was married to a man from Kericho. In Naivasha, the mother was a maid before she married Peter Amin, with whom they had two children, Stanley Amin’s sisters.

Amin didn’t know his relatives, and whenever he tried to ask for more information from his mother, “she always became harsh.” Attempts to get the information from his step-father bore no fruits, either.

When his father was shot, he was buried in a government cemetery as there were no documents to shed light on his identity, next of kin, or place of origin.

“When the police later came to search that evening, they only found a sack of sharp and crude weapons beneath the bed,” Amin said.

The neighbors, too, knew little about the family living next door and thus were of no help in the bid to establish the family’s background.

That evening, when his mother failed to return home, the neighbors took the three children to different homes, and the three siblings were separated. He only remembers his sisters’ names as Beverly and Alice.

A few days after the initial riots, another wave of bigger and deadlier violence than the former erupted. Friends and neighbors turned against each other, baying for one another’s blood like predators on prey in the animal kingdom. This second surge of turmoil saw his temporal foster home melt and disintegrate in the heat of brotherly love-turned hatred.

Amin was once again involved in the ugly incident that saw him fracture his head.

“They came from the opposite directions of our homes. People were running for their safety and I joined them. The neighbors who had taken in my two sisters also scampered for safety,” Amin said.

He said he had almost exhausted his energy when he saw a Red Cross pickup truck. It turned out to be his haven.

“There was a young lady just meters away from the pickup. I remember she held me roughly and threw me in the car. I landed by the back of my head, and I got injured badly,” he said.

The pickup truck collected children caught up in that violence and sped off to Ntimaru in Migori County. There, Amin says, they were taken to an orphanage. He stayed there for a year before a watchman at the institution adopted him.

“He was a humble, friendly man. He was vetted by the authorities at the facility, and he took me in to be his son,” Amin said.

“They came from the opposite directions of our homes. People were running for their safety and I joined them. The neighbors who had taken in my two sisters also scampered for safety,” Amin said.

The watchman’s family welcomed him. They even enrolled him at Matare Primary School, he said. However, trouble knocked at the child’s door when his foster father died three months after adoption.

“After mzee’s death, one evening, a meeting of the extended family was convened. I was not allowed to attend. I would later be called in to be informed that they could no longer continue hosting me as their child,” Amin said.

While in Naivasha, Amin had heard one of their neighbors say that Susan Aoko, his mother, had run away to her home in Mbita. Thus, when he was released from the late guard’s home, he saw it as a chance to go around the place to look for his mother.

He traversed the place on foot. Sometimes boda boda operators assisted him with shelter, food, and transport. As fate would have it, he arrived at a District Officer’s (D.O) office in Mbita. He told his story and how he was searching for his mother, believed to be in Mbita. However, the boy didn’t know Dholuo or his tribe.

The D.O. hosted him for a few days while they searched for his mother without much success. After the search for his mother failed, the D.O. released him but gave him a document.

“He wrote me a letter explaining my condition. He also recommended me for help and signed off with his details and contacts. He released me and said: ‘You can survive with this,'” he said.

LEAVE A COMMENT

You must be logged in to post a comment.